Cahoots Event Offer Terms & Conditions

-

The competition is open to all attendees of the Cahoots event at The London Library, including members but except The London Library employees.

-

There is no entry fee and no purchase necessary to enter this competition.

-

Entrants agree to the use of their email by The London Library for marketing purposes. Email addresses will not be passed to any third parties. Entrants may unsubscribe at any time.

-

By entering this competition, an entrant is indicating his/her agreement to be bound by these terms and conditions.

-

Only one entry will be accepted per person. Multiple entries from the same person will be disqualified.

-

Closing date for entry is Thursday 27 June 2019.

-

No responsibility can be accepted for entries not received.

-

The rules of the competition and how to enter are as follows: People must clearly write their email address on a slip of paper or keep in touch card and place it in one of the boxes.

-

Tickets for events must be booked in advance by emailing This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., the winner may bring one guest to each event but tickets are non-transferable.

-

The London Library reserves the right to cancel or amend the competition and these terms and conditions without notice. Any changes to the competition will be notified to entrants as soon as possible.

-

The prize is one year of 2x complimentary tickets to public events taking place at The London Library. London Library events being held elsewhere are not included within the prize.

-

The prize is as stated and no cash or other alternatives will be offered.

-

The winner will be chosen at random.

-

The winner will be notified by email within 28 days of the closing date (10pm 27 June 2019). If the winner cannot be contacted or does not claim the prize within 14 days of notification, we reserve the right to withdraw the prize from the winner and pick a replacement winner.

-

The London Library will liaise with the winner regarding booking tickets to events.

-

The winner agrees to the use of his/her name and image in any publicity material. Any personal data relating to the winner or any other entrants will be used solely in accordance with current UK data protection legislation.

-

Entry into the competition will be deemed as acceptance of these terms and conditions.

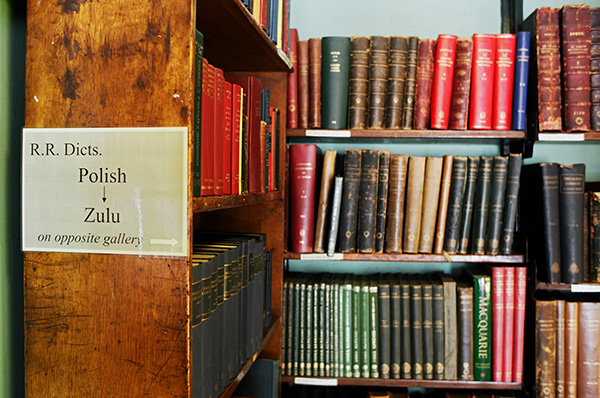

We have been looking at summers past – mining the borrowing records to compile the list of July and August’s 20 most borrowed books (Fiction and non-Fiction) over the past ten years.

Here's what we found:

FICTION

Wolf Hall, Hilary Mantel (London: Fourth Estate, 2009)

Journey Into Fear, Eric Ambler (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1940)

Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, Elizabeth Taylor (London: Chatto & Windus, 1971)

The Siege of Krishnapur: a novel, J.G. Farrell (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1973)

A Sport and a Pastime, James Salter (New York: Modern Library, 1995)

The Mandelbaum Gate, Muriel Spark (London: Macmillan, 1965)

An Officer and a Spy, Robert Harris (London: Hutchinson, 2013)

Stoner, John Williams; with an introduction by John McGahern (London: Vintage Books, 2003)

The Stranger's Child, Alan Hollinghurst (London: Picador, 2011)

Nocturnes: Five Stories of Music and Nightfall, Kazuo Ishiguro (London: Faber, 2009)

Scoop: A Novel, Evelyn Waugh (London: Eyre Methuen, 1978)

Orlando: A Biography, Virginia Woolf (London: Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press, 1928)

The Wedding Group, Elizabeth Taylor (London: Chatto & Windus, 1968)

The Radetzky March, Joseph Roth; translated by Eva Tucker (Harmondsworth : Penguin, 1984)

The Buried Giant, Kazuo Ishiguro (London: Faber & Faber, 2015)

The Green Hat: a romance for a few people, Michael Arlen (London: Collins, [1924])

Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand (New York: Signet, c1992)

The Bell Jar, Sylvia Plath (London: Faber, 1996)

Excellent Women, Barbara Pym (London: Cape, 1952)

Some Hope, Edward St. Aubyn (London: Heinemann, 1994)

NON-FICTION

Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947, Christopher Clark (London: Allen Lane, 2006)

Cairo in the War, 1939-1945, Artemis Cooper (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1989)

The Long Weekend: life in the English Country House between the wars, Adrian Tinniswood (London: Jonathan Cape, 2016)

Between the Woods and the Water: on foot to Constantinople, Patrick Leigh Fermor (London: John Murray, 1986)

A Time of Gifts: on foot to Constantinople: (London: John Murray, 1977)

East West Street: on the origins of genocide and crimes against humanity, Philippe Sands (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2016)

Outsider: always almost: never quite: an autobiography, Brian Sewell (London: Quartet, 2011)

The Wartime Journals, Hugh Trevor-Roper; edited by Richard Davenport-Hines (London: I. B. Tauris, 2012)

Vanished Kingdoms: the history of half-forgotten Europe, Norman Davies (London: Allen Lane, 2011)

Hugh Trevor-Roper: the biography, Adam Sisman (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2010)

Bloody Victory: the sacrifice on the Somme and the making of the twentieth century, William Philpott (London: Little, Brown, 2009)

A View from the Foothills: the diaries of Chris Mullin, Chris Mullins, edited by Ruth Winstone (London: Profile Books, 2009)

The Fall of Rome; and the end of civilization, Bryan Ward-Perkins (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005)

The last Bourbons of Naples: (1825-1861), Harold Acton (London: Methuen, 1961)

Religion and the Decline of Magic: studies in popular beliefs in sixteenth and seventeenth century England, Keith Thomas (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971)

Gladstone, Roy Jenkins (London: Macmillan, 1995)

Citizens: a chronicle of the French Revolution, Simon Schama (London: Viking, 1989)

Capital in the Twenty-first Century, Thomas Piketty; translated by Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge Mass; London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014)

One Hundred Letters from Hugh Trevor-Roper, edited by Richard Davenport-Hines and Adam Sisman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014)

An English Affair: sex, class and power in the age of Profumo, Richard Davenport-Hines (London, Harper Press, 2013)

Thank you for signing up to our newsletter.

We send a newsletter each month with information on upcoming events, Library news, special offers and updates from our partners. We hope you enjoy reading them.

The Books that made Dracula

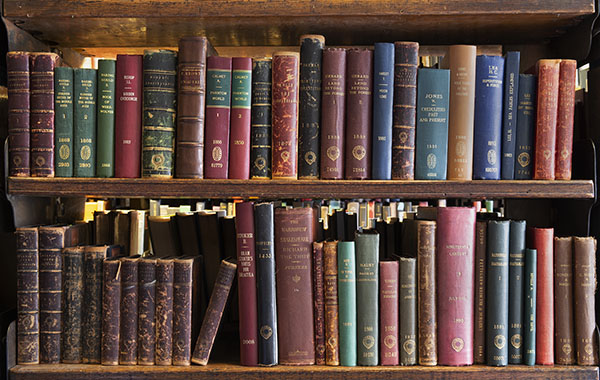

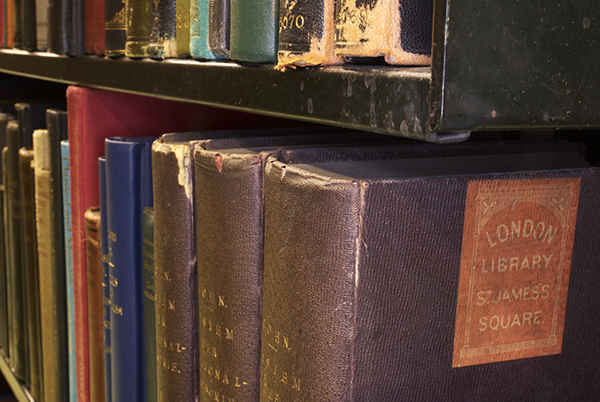

The London Library today unveiled a fascinating discovery that sheds new light on how Dracula was researched and written. We've found 26 books that are almost certainly the original copies that Bram Stoker used to help research his enduring classic.

Philip Spedding, the Library’s Development Director who made the discovery, commented: “Bram Stoker was a member of The London Library but until now we have had no indication whether or how he used our collection. Today’s discovery changes that and we can establish beyond reasonable doubt that numerous books still on our shelves are the very copies that he was using to help write and research his masterpiece.”

Philip’s detective trail began with the collection of Stoker’s handwritten and typed notes that had been discovered in 1913 but only published in facsimile form in 2008*. The notes list a wide range of Stoker’s sources for Dracula and include hundreds of references to individual lines and phrases that he considered relevant. A recent trawl of our shelves has revealed that the Library has original copies of 25 of these books, carrying detailed markings that closely match Stoker’s notebook references.

The markings range from crosses and underlinings against relevant paragraphs, to page turnings on key pages, to instructions to have someone copy entire sections into his typewritten notes.

Some of the most heavily marked books include Sabine Baring-Gould’s “Book of Were-Wolves” and Thomas Browne’s “Pseudodoxica Epidemica”. But the range of titles also sheds light on the detail of Stoker’s geographical and historical research – for example, AF Crosse’s “Round About the Carpathians” and Charles’ Boner’s “Transylvania”.

The suggestion that Stoker was using the Library heavily is given added weight by the timing of his seven-year membership which coincides almost exactly with the period when he was working on Dracula and beginning to develop an active writing career alongside his already very successful role as theatre manager at The Lyceum Theatre. Earlier research by our Archive Librarian Helen O’Neill showed that he joined in 1890, the year he visited Whitby and first developed the idea for his vampire story, and he finally left the Library in 1897, the year Dracula was published. His membership form is seconded by his close friend Henry Hall Caine, a bestselling author of the day, a London Library member, and the man to whom Stoker dedicated Dracula, using Hall Caine’s nickname “Hommy-Beg”.

Philip Spedding continued, “It is almost certain that the books we have found have been marked up by Bram Stoker himself and that he drew heavily on The London Library’s collection to help research Dracula. Indeed, it is not fanciful to suggest that his extraordinary tale of the Transylvanian undead has many of its origins in the quiet confines of St. James’s Square.”

Professor Nick Groom from Exeter University and a leading expert on gothic literature said, “This is a very exciting discovery. I have examined the books and their annotations with Philip Spedding and have compared them with Bram Stoker’s own notes. I am in no doubt that Bram Stoker used these very copies for Dracula – a book that took him seven years to write. They demonstrate that The London Library was the crucible of one of the most influential novels in world history.”

Philip Marshall, Director of The London Library concluded: “Bram Stoker followed the same path that many writers have pursued before and since - using the Library to transition into a serious writing career, and drawing heavily on the Library’s collection to seek inspiration and ideas for his masterpiece. With the Library’s incredible list of members past and present, some of the most famous characters in fiction must have been developed here – with today’s discovery we can feel sure that Dracula was one of them. We hope that many aspiring writers will follow Bram Stoker’s example and use The London Library as a source of inspiration and support when creating their own masterpieces.”

Watch the video as Philip Spedding tells the story behind an amazing discovery, alternatively view it here.

The Books That Created Dracula from The London Library on Vimeo.

Books referenced in Stoker's notebooks that are still on our shelves

- Nineteenth Century XVIII, Mme Emily de Laszowka Gerard, Kegan Paul, Trench & Co, July 1885 The Book of Were-Wolves, Sabine Baring-Gould, Smith, Elder and Co, 186 Pseudodoxia Epidemica,Thomas Browne, 1672 Magyarland, Nina Elizabeth Mazuchelli, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1881 The Golden Chersonese, Isabella Bird, John Murray, 1883 Round about the Carpathians, AF Crosse, Blackwoods, 1878

- On the Track of Crescent, Major EC Johnson, Hurst & Blackett, 1885

- Transylvania: Its Products and Its People, Charles Boner, Longman, Green, Reader & Dyer, 1865

- An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, William Wilkinson, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1820

- Curious Myths of the Middle Ages (2 vol), Sabine Baring-Gould, Rivington, 1868

- Germany Past and Present (2 vol), Sabine Baring-Gould, C Kegan Paul & Co, 1879

- Legends & Superstitions of the Sea, Bassett The Origin of Primitive Superstitions, Dorman, Lippincott, 1881

- Credulities Past & Present, W Jones, Chatto & Windus, 1880

- The Folk-Tales of The Magyars, The Rev W Henry Jones and Lewis L. Kropf, The Folk-Lore Society, 1889

- Superstition & Force, HC Lea, Lea Brothers & Co, 1892

- Sea Fables Explained, Henry Lee, William Cloves & Sons, 1883

- Anecdotes of the Habits and Instincts of Birds, Reptiles and Fishes, Mrs R Lee, Grant & Griffith, 1853

- The Other World; or, Glimpses of the Supernatural. Being Facts, Records, and Traditions, FG Lee, Henry S King & Co, 1875

- Letters on the Truths Contained in Popular Superstitions, Herbert Mayo, Blackwood, 1849

- The Devil: His Origin, Greatness and Decadence, Rev Albert Réville, Williams & Norgate, 1871

- A Tarantasse Journey through Eastern Russia in the Autumn of 1856, W Spottiswode, Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts Miscellany, W Spottiswode Traité des Superstitions qui Regardent les Sacraments (4 vol), Jean-Baptiste Thiers, Louis Chambeau, 1777

- The Phantom World: or, The Philosophy of Spirits, Apparitions &c. (2 vol), Augustin Calmet, Richard Bentley, 1850

- The Land Beyond the Forest (2 vol), E Gerard, William Blackwood & Sons, 1888

Other books on the Library’s shelves not referenced in Stoker’s notebooks but containing comparable marginalia

- On the Truths Contained in Popular Superstitions with an Account of Mesmerism, H Mayo, William Blackwood & Sons, 1851

- La Magie et L'Astrologie dans L'Antiquité at au Moyen Age, Didier et Cie, 1860

- Anecdotes of the Habits and Instincts of Animals, Mrs R Lee, Grant & Griffith, 1852

- Narratives of Sorcery and Magic (2 vol), Thomas Wright, Richard Bentley, 1851

- Things not Generally Known. Popular Errors Explained, John Timbs, Kent & Co, 1858

- Roumania Past and Present, James Samuelson, Longmans, Green & Co, 1882

Books referenced in Bram Stoker’s notebooks no longer on the Library’s shelves

- A Glossary of Words used in the Neighbourhood of Whitby, FK Robinson

- The Natural & Supernatural of Man, John Jones,

- History & Mystery of Previous Stones, W Jones

- Superstition Connected with Hist & Medicine

Books referenced in Bram Stoker’s notebooks never held by the Library

- Fishery Barometer Manual, Robert Scott

- The Theory of Dreams (2 vol), FC & J Rivington, St. Pauls Churchyard, 1808

- Sea Monsters Unmasked, Henry Lee

- A report in IBIS on "The Birds of Translyvania", Danford and Brown

* ‘Bram Stoker’s Notes For Dracula’ was published in 2008 in a facsimile edition annotated and transcribed by Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller